Jay Camille Interview

By Max Winkelman

Photo by Tina Lovgreen/CBC

Jay Camille was in Chilliwack on Friday, July 7 for a pipeline project for the same client they were working with on a two-kilometre pipeline replacement project on Soda Creek Indian Band reserve.

“I got a call that there was smoke billowing from every direction from the guys that were on the reserve here. The initial call was that they saw smoke on the horizon and then I talked to my wife in Williams Lake and she says, ‘yeah we can see three different spots of smoke from out place in Williams Lake.”

Camille had been around forest fires a lot as a helicopter pilot, which is where he got most of his flying experience.

“I knew the severity of what could happen. I had seen enough fires, not around cities like this, but in the Chilcotin region back in 2009 and 2010 it was pretty extreme fire behaviour and to see that same fire behaviour and the fir timber type on the east side of the Fraser River was really, really scary.”

Camille got his family out of town quickly, so he didn’t have to worry about them before joining suppression efforts.

“My initial response was ‘wow’ because I saw some pictures of the black columns and from my previous fire experience, I knew that black was hot, hot,” he says. “To have that sort of activity within an hour after the lightning strikes was unbelievable. So fear I guess, for sure, because you kind of knew what potentially was coming.”

Camille took a hydroseeding truck, which is essentially a 1,500-gallon water tender, from the Chilliwack pipeline operations and started driving back home.

With the truck and the help of the Cariboo Fire Centre who he was in contact with and who knew he was bringing a water tender up to come help, he managed to get past 108 Mile Ranch where the Highway was closed because of the Gustafsen fire.

“They helped me get through the closures in 100 Mile.”

Camille said when he made it back, it was chaos everywhere with people filling up vehicles.

The next morning, he started getting his equipment ready to go when he got a call from Enbridge. Enbridge was doing pipeline work on the reserve and, upon receiving a call from the Band, got in touch with Camille.

“At that point in time, even on Saturday morning, I hadn’t heard about the fires on the Deep Creek Reserve yet. So what I did is hopped into my one water tender and I drove out here not even knowing where the fires had started or were. I drove up Mountain House Road and that’s where I ran into Kelly Sellars and the crew that was already starting the suppression effort with his tractor and tenders and the guys that he had.”

He communicated and coordinated with them to get pumps and hoses set up and also got some of his crew to come out and help after seeing the severity of what was happening.

He then called the pipeline company, Triple J Pipelines, and asked if he could borrow some of their bulldozers. They told him to go for it. He called his dad had a low-bed to help transfer the dozers from the pipeline project to where the suppression efforts were.

“I started pushing guard with the dozer but again back to my prior experience, I knew that it wasn’t safe to be just sending a dozer in with that kind of fire activity on the side of a mountain because the fire activity is crazy on the side of a mountain. It’s more reactive and explosive just because of the way it dries out the fuels ahead of the fire head.”

He called the Cariboo Fire Centre (CFC) back, who he had a longstanding work relationship with, and told them, “look we have a big fire out here. We have no help. We need a helicopter to get up and look at what we’re dealing with.”

The fire centre told him they had no resources available as far as manpower to send out but offered pumps, hoses and anything they might need, he says.

In talking to the CFC, they told him they had nobody to manage the fire and asked Camille if he would take charge of the fire based on his previous experience as a helicopter pilot on wildfires. Camille said ‘yeah sure” at which point he became the incident commander on the fire.

Camille then went and talked to the Band Council to get their approval for him to lead suppression on the fire (the Band and the BC Wildfire Service have a shared agreement that allows for fire suppressions activities on federal land). After they said yes, they also got a helicopter to keep an eye in the sky on the bulldozers as well as for Bambi bucketing to keep it cool as they were pushing a guard along the side of the fire.

Normally, the protocols are that the government hires the people and the equipment but between being on Reserve and the CFC being so overloaded, they started putting together their own team.

“We had no certainty because we weren’t under the fire centre’s system. So at that time, that’s when I said to Council here, ‘we’re hiring these people to come help, who’s paying for it? Because it’s not going through the fire system,” says Camile. “The Band, they said, ‘yeah, we will pay anybody to come and help us.’”

That gave Camille the resources to come and help. Kelly also started getting more people together on his crew. It took a few days to get things properly organized, says Camille.

“A couple of days in, we still had guys in running shoes and no hard hats out there trying to fight the fire. I said ‘Woah, we need to slow down here a little bit and keep everybody safe. That’s number one.”

At that time, people from the Band went to town to buy hard hats, work boots, vests and other supplies.

Their initial team consisted of six dozers, 20-25 firefighters and a medium bucket ship. Camille says he was really happy the CFC sent out a helicopter because that’s outside their normal protocols.

“Usually to send out a helicopter, they need a fire centre staff representative there to keep that helicopter safe. That was one of the things that I’m thankful for. They had enough t

rust in me and they said, ‘Jay, we know you’re not going to go and do something stupid with this helicopter because you’ve flown them and you’ve been around them.’”

Camille was able to get up between some of the fuel cycles to have a look at the fire to start planning and coordinating the crew.

“Usually, a fire of that size, you would have 100 people easily on it… We just had to start with what we had and what we could find.”

The main priorities were the houses and trying to come up with a plan to guard the west-side of the fire, he says.

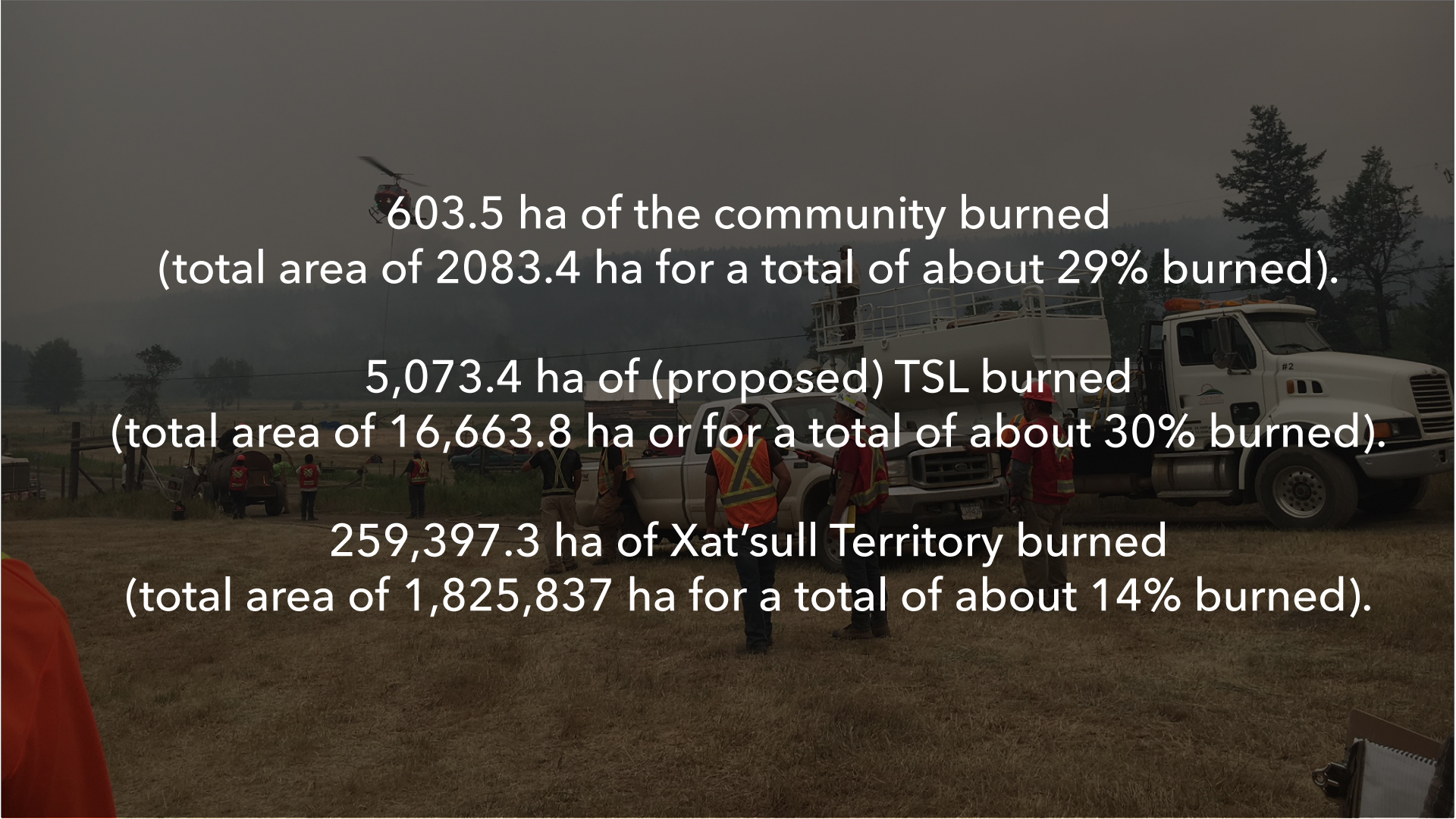

In the first week, they got a lot of fireguards put in and extinguished a lot of fire within the perimeter of the fire.

“We probably had about 70 per cent of the fire guarded, the initial fire in that first six days. We were working on just tidying up some edges, tidying up some lines so that there weren’t some gaps between the fires and where our guard was.”

“The wind had picked up in a matter of minutes it felt like and the fire was now in the crowns of the trees and running,” he says. “All those people out there were my responsibility and it was the scariest day of my life, I think. It was insane …”

The following Saturday they’d predicted increased winds. Camille says he’d been extra careful with where he’d put the crews that day and with where he put the dozers.

The following Saturday they’d predicted increased winds. Camille says he’d been extra careful with where he’d put the crews that day and with where he put the dozers.

It was about 3 in the afternoon when the helicopter put him down, after being in the air all morning, at their staging area in the Deep Field Reserve hayfields.

The helicopter went back to the Williams Lake airport to refuel while Camille sat down to have lunch that the community provided every day.

“They were bringing lunches and dinners and it was a great part of that first week. We were well fed, having lunch, and I noticed the wind kind of picking up a little bit,” he says. “This was only half an hour, maybe 20 minutes since I’d just been in the air and everything was calm and everybody was where they should have been and people were working hard.”

Camille decided he’d better go for another flight, so they took right off again when the helicopter came back and as they came over the hill to the northeast side of the fire it was just blowing up.

“The wind had picked up in a matter of minutes it felt like and the fire was now in the crowns of the trees and running,” he says. “All those people out there were my responsibility and it was the scariest day of my life, I think. It was insane. The crews had already noticed and had been calling be on the radio as I transferred into the helicopter and the fire was running through the crowns and I was trying to get the crews out to start evacuating and some of them were already on their way out. The others were started evacuating out heading for the south side, so back to Mountain House Road. I made the order for everybody to evacuate off the fire.”

The fire was moving through the crowns way faster than you could have ever outrun it on foot, he says. CFC Initial Attack crews were dealing with a small spot fire about five kilometres to the north of the boundary of the Deep Creek fire.

“They were down in the timber and it was a really calm day. Everybody was comfortable about six days since the big blowup and the McLeese Lake Fire Department and that [CFC] Crew had asked me for a dozer that morning. So I’d sent one of our dozers up there to put in guard and they couldn’t see what was coming. They had no vantage point. They had no helicopter in the sky. So I’m on the radio just trying to call and it was a good friend of mine that was running the dozer for them. I couldn’t get him on the radio and finally, we were right over top of him and I could see this wall of flame coming at their fire, coming at their location that had jumped our guard and was taking right off. [I] told them what was coming; evacuate now to the north,” he says. “I get him on the radio ‘start walking [the dozer] out quickly now. This fire’s blowing up. We’ve got to get you out of there.’ He’s walking it around… Watching him from the helicopter it felt like it was so slow.”

Camille looked at the wall of flame that was coming and says he knew he didn’t have time to get back to the initial point of the guard.

“I told him, ‘turn left. There’s a power line in about 150 metres. You’re just going to have to go through that timber.’ He heard the urgency in my voice.”

By that time the McLeese Lake fire department and the rest of the crew were out and evacuating out to the north but Camille’s friend was still in the dozer way back by himself.

“He just crawled through all this timber,” Camille says which the dozer wasn’t very happy with. “It was either that or for sure the machine would have burned. He crawled through the timber, hit the powerline.”

At that point, Camille told him to drive down the powerline and to make a safe zone (fireguard around the bulldozer). Next, he told him to leave the machine.

“I said, ‘there’s a little landing spot. We can pick you up just in from the timber. I said ‘we’ll hover over here. Just run, leave the dozer, run, jump in with us’ and, we got him out of there,” he says. “While we were waiting for him to do that, there’s a … powerline that runs to the north up by Forrest Lake. It’s a big powerline and we watched the wall of flame come and it hit that powerline and I’ve never seen anything like it. When it hit the powerline, you could see electrical currents up in the smoke and it was like lightning but as that fire hit the powerline it arched through the flame and the fire. It was like ‘bzzzt’ and then all of a sudden just done. That fire ran over that powerline and just kept roaring to the north.”

“That initial flareup from that wind, it was so close and it was my responsibility so it was a day I’ll never forget.”

The bulldozer did survive the whole ordeal.

“The cool part about it was how the community came together and worked hard… that was something that will always stick with me that spirit that came from the Xat’sull people.”

Usually, the CFC only lets crews in this capacity work 14 days so on day 15, they had someone come in from the fire centre to replace him, says Camille.

“That’s when I kind of stepped back from that initial role as one of the division coordinators and that’s when a lot of the accounting and paperwork took over from the fire centre from the initial responsibility that I made to the community here. So that’s kind of how that transition happened from community to the fire centre.”

Looking back, it’s amazing how the community of Xat’sull came together, says Camille.

“From the women and people helping supply us with food to the people, the community members who stepped up to volunteer,” he says. “I had folks there taking names, numbers, addresses, you know all the information before we sent them out and we, at that time had designated crew bosses, squad bosses. The cool part about it was how the community came together and worked hard… that was something that will always stick with me that spirit that came from the Xat’sull people.”

Camille says he’s pretty proud that he was able to participate and able to help structure, coordinate and save houses with their effort.

“I grew as a person a lot too through that time I think.”